- With a population of around 1,500, Morop Tarambas is a natural resource with untapped potential. It’s a site for hiking, healing, and heritage. It’s a place where conservation is not a policy it’s a practice. Where spirituality is not separate from ecology it’s embedded in it.

In Baringo Central, exists a sanctuary where conservation, culture, and community converge: Morop Tarambas Conservancy. One of 16 conservancies in the county, it’s more than a patch of protected land. It’s a living archive of biodiversity, a spiritual shrine, and a civic resource stewarded by the people who call it home.

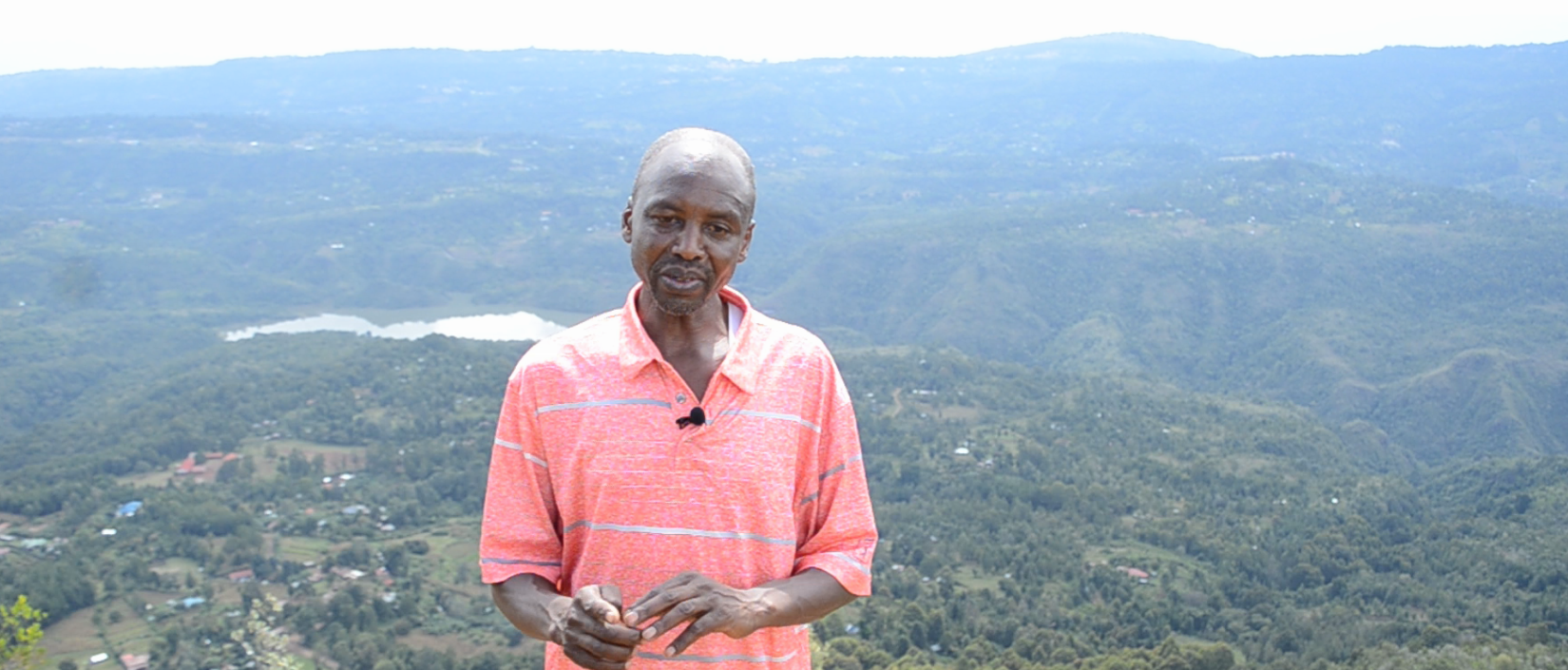

Founded in 2005 and officially registered in 2010, Morop Tarambas spans 21 hectares of sacred terrain. Just 13 kilometers from Kabarnet town, the county headquarters, it rises to a dramatic 2,333 meters above sea level, its hilltop famously shaped like an elephant.

From here, Baringo unfolds in every direction: Lake Baringo, Lake Bogoria, Lake 94, the shimmering Kimao and Chemeron dam, the bustling Kimalel goat auction, and the meat markets of Koriema. You can trace the contours of Kirandich Dam, Kabarnet town, Kimochoch, Saimo, and the full stretch of Ewalel Chapchap from Talai.

But Morop Tarambas is more than a view, it’s a vision.

Every Easter, Christians ascend the hill to pray. The land is revered as a spiritual site, where old women and men gather herbs to heal mothers and children. “We still have herbalists,” says Rodgers Komen, the conservancy manager. “The chances of a mother needing a C-section are rare here. Medicinal plants still serve our people.”

Read More

This is a place where therapy doesn’t come in pills or prescriptions, it comes in sweat, silence, and sacred walks. “People hike to reduce blood sugar and pressure,” Komen adds. “The terrain itself is medicine.”

Morop Tarambas is a conservancy in the truest sense, land voluntarily set aside for wildlife, eco-tourism, sustainable farming, and cultural preservation. Legally recognized under Kenya’s Wildlife Act of 2013, it’s a model of community-led stewardship.

“We do conservation through education,” says Komen. “We protect indigenous trees and shrubs, many of which are medicinal. We even have sandalwood—an endangered species.”

Elias Rotoich, a local resident, echoes this: “This forest helps us. We use it for medicine, for circumcision rituals, for building homes. It feeds our water sources like Kirandich Dam.”

Benjamin Brachebo, another resident, describes the community’s farming method: “We use the shamba system. We plant maize and other crops, but we avoid cutting trees. We value the forest.”

Morop Tarambas is not an isolated effort, it’s part of a national movement. Conservancies like this one Preserve biodiversity, protecting endangered species and plants. They also support livelihoods through eco-tourism, sustainable agriculture, and cultural heritage.

Furthermore, they Restore ecosystems, improving soil health, water retention, and climate resilience. They also empower communities, giving locals a stake in the land they live on.

They’re central to Kenya’s biodiversity strategy, aligned with Vision 2030, and vital to global conservation goals.

With a population of around 1,500, Morop Tarambas is a natural resource with untapped potential. It’s a site for hiking, healing, and heritage. It’s a place where conservation is not a policy it’s a practice. Where spirituality is not separate from ecology it’s embedded in it.

And above all, it’s a reminder: that the land we protect, protects us in return.

Follow us on WhatsApp for real-time updates, community voices, and stories that matter.

-1768824505.jpg)